A Brief History of Common Games (1)

Major disclaimer

This is a post about some of the history behind the solvability of a few common games.

It should be very understandable for people without a math background, as there isn’t any real math in here.

An introduction

Games are the perfect mix of chaos and strategy: games are dynamic, since players’ decisions affect them, but there often exists an optimal way to play. So, let’s study a few simple games most people have played and examine:

-

why we can solve some games but not others

-

how we solve these games

-

some different processes which were developed along the way

I’ll focus on tic-tac-toe and set take-away, but also briefly discuss Connect 4, checkers, and chess.

Types of games

Let’s begin by explaining different classifications for games and developing basic definitions that become relevant when examining games. In game theory, a player demonstrates perfect play when they play the game in such a way that their strategy leads to the optimal result, no matter what strategy the opponent is using. Games are classified into either being solved, partially solved, or unsolved. The names are pretty self-explanatory:

-

A solved game has an outcome (win, lose, or draw) that can be determined from any position, given perfect play by both players. Perfect play is required because it controls the game so that only optimal moves are made.

-

A partially solved game has an outcome that can be determined from some starting positions, but not from others.

-

In an unsolved game, the game’s result cannot be determined from any starting position.

Solved games have three subsets: ultra-weakly solved, weakly solved, and strongly solved. In an ultra-weakly solved game, it can be determined whether the first player will win, lose, or draw from their initial position. For a weakly solved game, there exists an algorithm for at least one starting position of the game, where a win or draw is guaranteed for a player. Lastly, a strongly solved game has an algorithm such that a player can play an optimal solution (I didn’t say “win” because the optimal solution could be a draw from certain positions) from any starting position.

Wow weren’t all those definitions super fun!? Sorry about that, but don’t worry because next come examples, which will help everyone be able to differentiate all these different types of games.

Tic-tac-toe

One example of a strongly solved game is tic-tac-toe. Perfect play from both players leads to a draw, which is known as a cat’s game.

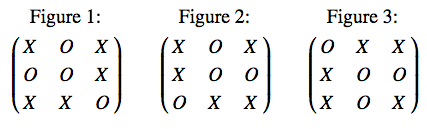

Since tic-tac-toe is played on a symmetric grid, it’s easy to overcount the set of board outcomes. For example, figure 1 is a reflection of figure 2 and figure 3 is a rotation of figure 2, so we wish to consider all three of those boards the same. After considering and discounting board symmetries and assuming \(X\) plays first, there are exactly 91 winning board positions for \(X\), 44 winning board positions for \(O\), and 3 board positions that are considered a draw. The total possible positions in tic-tac-toe is 765. This number is interesting to keep in mind because it’s significantly smaller than the total possible positions in other games we’ll look at later.

Tic-tac-toe has 8 simple rules, ordered in the importance that they should be followed. When a player uses the first applicable rule in the list for every turn, perfect play exists.

-

If you have two of your own mark in a row, place a third mark in the row to win.

-

If an opponent has two in a row, place a third in line to block the opponent’s win.

-

Create two unblocked lines of two in a row. This is called a fork.

-

Block an opponent’s fork by either forcing the opponent to defend by placing two in a row, or blocking the fork ahead of time.

-

Play the center.

-

If opponent is marked in a corner, play the opposite corner (the corner on the same diagonal).

-

Play a corner.

-

Play the middle of any of the four sides.

Connect 4

What’s interesting about the strategy behind tic-tac-toe is how it relates to more complex strongly solved games, like Connect 4. There are approximately \(10^{13}\) possible positions in Connect 4, which is significantly larger than the 765 possible positions in tic-tac-toe. Connect 4 was first solved mathematically in 1988 by James Allen.

Also in 1988, Victor Allis proved that if both players behave optimally in a game of Connect 4, the first player can always win if she starts in the middle column, and can at least draw if she starts in a column other than the middle column. I decided to look at Victor Allis’s method of solving Connect 4 because it’s similar to how tic-tac-toe is solved. Victor Allis developed 9 strategic rules to optimally play Connect 4. These rules can only be applied by the player who guides the game so that she controls which squares each player will mark (this is called controlling the zugzwang). Based on the description of the board, one of the rules is applied by a simple search of the board for which rule is applicable where. The rules focus on how to gain control of certain areas of the board.

Both the strategies given by Allis for Connect 4 and given above for tic-tac-toe are called knowledge-based approaches. In knowledge-based approaches there are a set of rules and facts that can be applied in order to play optimally. These rules are applied by searching the game board after each round and deciding which strategies are applicable. This technique works for many strongly solved games which have a relatively small number of possible board outcomes.

Chess and checkers

The solvability of chess and checkers are semi-interesting computationally and pretty boring mathematically. However, it’s helpful to consider them in order to understand why they are so difficult to solve. Both of these games have an immensely larger number of unique ways to be played as compared to Connect 4 or tic-tac-toe.

Currently, checkers is weakly solved and chess is partially solved. Checkers is categorized as weakly solved because from the standard starting position, when both players utilize perfect play, they will achieve a draw. Checkers was solved by Jonathon Schaeffer in 2007, almost 20 years after Allis solved Connect 4. To date, checkers is the solved game with the largest number of possible solutions to win, approximately \(5 \times 10^{20}\) unique ways. It’s the most complicated game solved, with a total of \(10^{14}\) total computations performed over the span of 18 years (I think. There’s very likely something new I don’t know about. This was true in fall 2012.).

It’s widely accepted that chess is not even possible to solve until a breakthrough in computing occurs, as there are an estimated \(10^{45}\) unique ways to win chess. Chess is partially solved because its endgame can be solved with perfect play once there are less than 6 pieces left on the board.

Subset take-away

Saving the most theoretically interesting bit for last, let’s end with a short discussion on an unsolved game. Remember that in an unsolved game, the outcome cannot be determined from any starting position. Subset take-away is a game in which two players alternate choosing proper subsets (this means you can’t take the whole set) of a particular finite set. Once a subset has been chosen, none of its supersets (sets which contain it) can be chosen by either player and no player can choose the empty set. The player who is left with no subset to choose loses. It’s been shown by Christensen and Tilford that when the game is played on a set with 6 or less elements, player 2 has a winning strategy. Furthermore, the creator of the game, David Gale, conjectured that player 2 always has a winning strategy in subset take-away. Still, the game remains unsolvable for any set larger than 6.

Subset take-away becomes equivalent to a technique known as simplex erasure. For the purpose of explaining this game, a simplex is the smallest convex shape that can be made from a set of vectors. So the simplex for 3 vectors is a triangle. In simplex erasure, one of the components of the simplex is erased, which represents a subset being chosen. In 1997, J. Daniel Christensen and Mark Tilford used this method to simplify the analysis of subset take-away for sets of cardinalities 5 and 6. Subset take-away is easily solvable by brute force for sets of size 4 or less.

An easy “take-away”

As the growth in technology continues, our capabilities to examine the large number of outcomes for different games grows, and this allows us to consider the solvability of complex games like checkers and chess. However, even with this growth, the computational power is not enough to solve some games, such as subset take-away. Different ideas are still being formulated to solve these games, but at the end of the day, more theory and strategy is needed when computation is not enough. (Or at least that’s what the mathematician in me says. A computer scientist might tell you I’m wrong.)

If you enjoy learning about games, let’s turn this subject more mathematical and talk about nim. Check out the post on it.